Trump's immigration agenda is not popular

Polling shows most Americans oppose the details of enforcement and the president’s most extreme tactics

To start this post, I am going to ask you a key question about immigration policy. But first, I need to establish a few facts based on recent news:

On Monday, April 14, 2025, Donald Trump met with the President of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, in the Oval Office. There, they jointly refused to facilitate the return of a legal resident of Maryland named Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who was illegally sent by Immigration and Customs Enforcement to a prison in El Salvador despite being protected by a U.S. court order from being deported to the country. ICE sent him there anyway and later admitted wrongdoing, and the Supreme Court has said Trump should help get Garcia back. Trump defied SCOTUS in the Oval.

Before the meeting, Trump told Bukele he would also like to ship U.S. citizens to the same prison Abrego where is now being held. The prison, called Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT), is really more like a camp of multiple airplane-hanger-like shelters lit by artificial light 24 hours a day and where solitary confinement is a common practice. Inmates get 30 minutes outside thee cells each day. The summary removal of U.S. citizens to a foreign jail without due process of law is likely illegal — to say nothing about the cruel and unusual conditions.

Previously, Trump had reportedly paid Bukele $6 million to house Venezuelan immigrants who ICE allege to be members of a gang called Tren de Aragua. Some of those sent to the CECOT prison, without a court hearing, were also sent in violation of U.S. court orders.

Now, here's the question: How popular do you think this all is? The question may sound trivial in the face of civil rights violations across the country — and, indeed, a full-blown constitutional crisis if Trump continues to defy the courts and not bring Garcia home.

But it is important to get the answer to this question right, for two reasons: First, because public opinion properly quantified holds an innate power in a democracy, and Trump clearly cares about his popularity; and second, because the media has largely covered Trump as carrying out a popular immigration agenda, and that framing is useful to the White House in defending its agenda.

The reality, though, is that what Trump is doing is not popular, once you dive into the specifics. This little nuance about immigration polling is so significant — the gap between broad and narrow opinion on the issue so large — that it has the power to shape the future of political conflict over immigration policy in America.

I. Trump is popular on "handling immigration," but not specifics

Read enough polls and you will come across some form of the following question:

"Would you say you approve, disapprove, or are you not sure about how President Donald Trump is handling the following issue?"

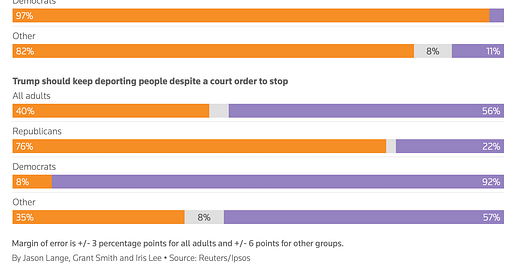

Where respondents are then read a list of options such as "immigration," "the economy," "foreign policy" etc. Results are usually presented in a list of most to least popular "issue approval," like the following chart from a Reuters report:

This question is fine if it's all you have, but there is a dramatic amount of nuance being washed over with the binary yes-no framing and use of such broad topics. What if the pollster asked about “immigration and civil rights,” for example? Or a more precise question that informed respondents what the administration is doing?

You might take away from this, for instance, that Americans approve of Trump's actions to deport Abrego Garcia and refuse to bring him home. That would be wrong though, as the same Reuters/Ipsos poll even goes on to show.

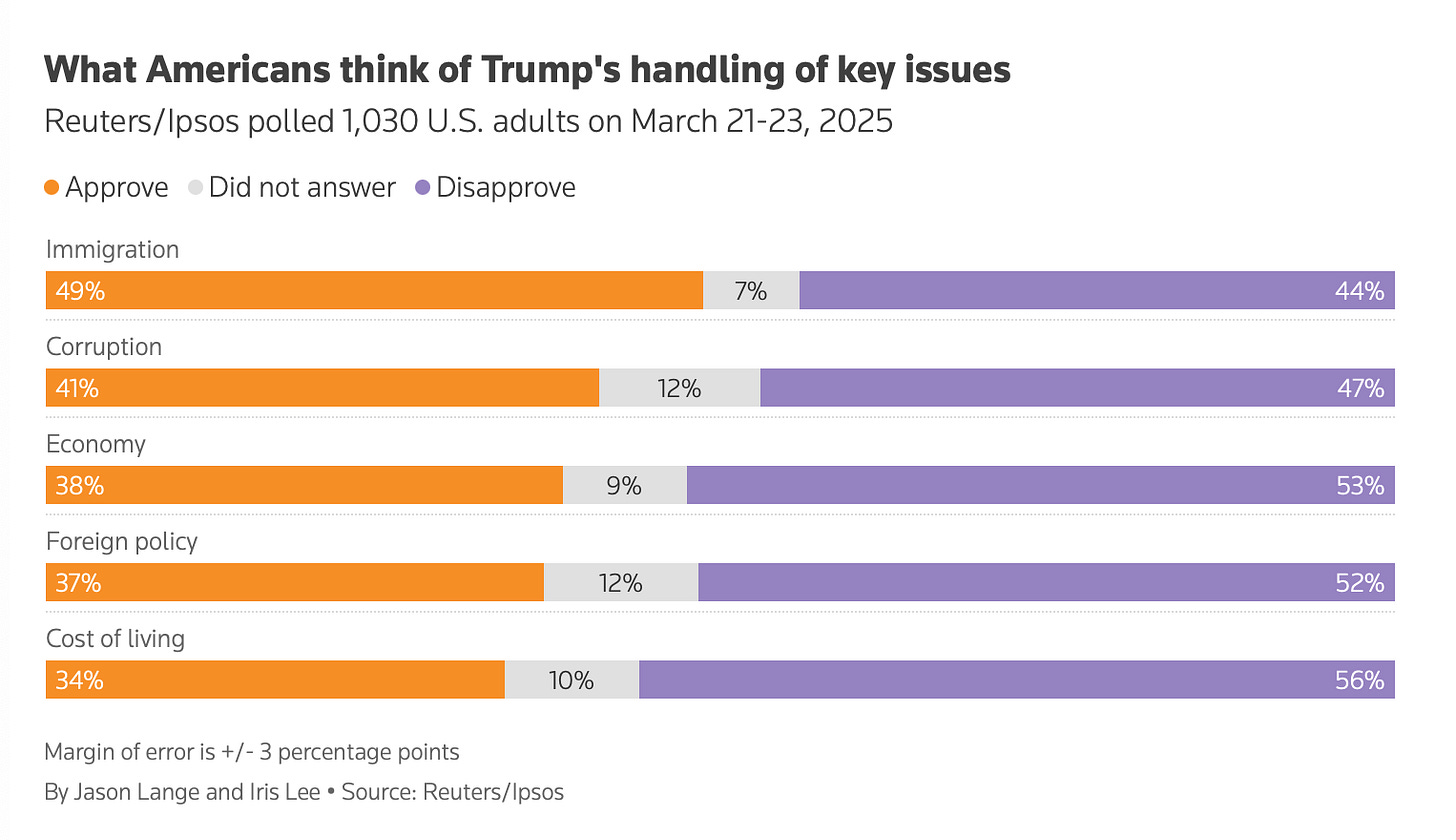

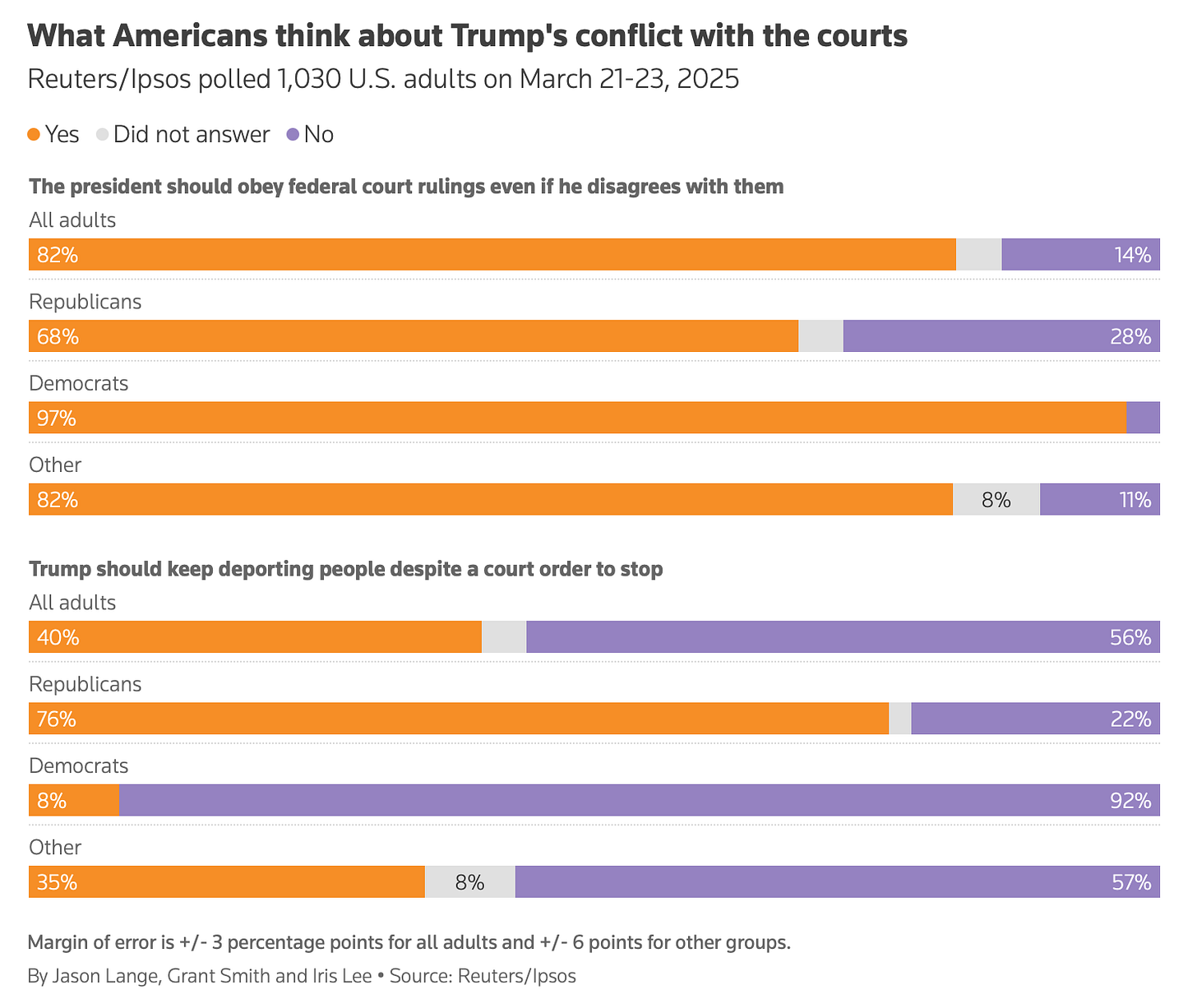

The vast majority — 82% — of Americans believe Trump should obey court orders even if he disagrees with them, and 56% think he should stop "deporting people" (again, very vague) specifically:

But the details of the policy Trump is carrying out are even more removed from the polling — even more unpopular, reflecting deep reservations among the public about what the president is doing.

For example, when various pollsters asked if they would support deporting immigrants who have been here more than 10 years (as in the case of Abrego Garcia), U.S. adults said "no" by a 37 percentage point margin; Americans disapprove of deporting immigrants who have broken no laws other than laws governing entry; they oppose deporting U.S. citizens convicted of crimes to foreign jails, such as CECOT, and they oppose housing migrants at Guantanamo Bay while they are processed. All of these are policies the Trump administration has now floated or is actively carrying out.

The only policy Americans really favor is deporting unlawful immigrants who have been accused of violent crimes. (And here, they are not asked about support for deporting them to prison without natural light from which they will never be able to escape again.)

Republicans may argue against this (and Stephen Miller has) that the details don’t matter if the signal on the broad question is strong enough. I think that’s a particularly vacuous form of spin; what is an issue area if not an aggregation of its component policies and actions?

The other counterargument I hear is that voters don’t support Democratic policies on the border and immigration, or else Kamala Harris would be president. To them I say it’s possible for people to dislike two things at once!

II. There is opportunity in overreach

Donald Trump has made a series of missteps over the last couple of weeks. Voters are now souring on him on the economy and inflation, for example, and his tariffs are deeply unpopular, too. You can add Monday's Oval Office meeting to this list.

The media narrative is that "Trump is popular on immigration." But as we can see, that is not really true. On the specifics of his policy, and especially on the on-the-ground implementation, Americans are mostly opposed to what his administration is doing. (And the data above should probably be considered an overestimate, since the polls I've used are old and conducted before the Abrego Garcia news.)

In other words, Trump's critics have an easy opportunity to fight the president in the court of public opinion. Americans do not approve of abducting fathers who have been in America for decades and sending them to torture camps in the jungle; And, contra Trump's wishes, they also oppose the extrajudicial transfer of U.S. citizens convicted of crimes to foreign jails.

And while I generally try not to engage in partisan cheerleading here, the reality is that Republicans are united in support of Trump, and since we have a two-party system, Democrats are the only options for recourse on civil rights and the rule of law. This issue really isn’t about Trump or immigration at all anymore, it’s about the Constitution itself.

The Trump administration so far has gotten away with denying Abrego Garcia and other legal residents of the U.S. their constitutional rights of habeas corpus. Now, the Executive is asserting that it can violate court orders with impunity and that it wants to do the same for trouble-making U.S. citizens. If you stand for the constitution, the rule of law, majoritarianism, and just generally treating citizens with dignity, there is really only one option for you, even if you try to approach politics from an unbiased perspective, as we do here at Strength In Numbers.

So not only does the party currently have public opinion on its side, I think Democrats also have an obligation to speak out on moral and constitutional grounds. And, given the data, they have a clear opportunity to take bold action. That could be anything from a campaign for immigrants’ rights and the rule of law, to a more fleshed out immigration policy (something voters trust more than what the party has recently advocated.)

As I cover in my book on polling and democracy, legislators generally exist somewhere along a spectrum running from two theories of representation for constituents: They can lead, or they can follow. The political scientist Lindsay Rogers, a polling skeptic, decried the rise of public opinion polls in media and government as "government by poll." Rogers feared polls would push legislators into the follower camp, leading to a generation of elected politicians who lacked the skills of leadership and judgment. In this case Democrats conveniently don't have to pick: The clear option is to do both. Americans are with them. Rogers may say this is a rare opportunity to lead the public when it has already told you it wants to follow. Easy W.

Based on the data above, you can argue Democrats should try take the horns on immigration. Go big on common-sense reforms that protect civil rights for people who have been here long enough and not broken laws. Reach out to moderate Republicans who are concerned about Trump for a pathway to citizenship. Join publicly with the Supreme Court and rally in the street for deported residents and snatched-up tourists.

Fighting is what democracy is for, after all. And if nobody is willing to fight for the Constitution, we don’t have a democracy anymore anyway.

The fact that immigration is one of the few issues were Trump is still "above water" is mostly a testament to the public's lack of confidence in the Democratic Party to deal with immigration. Trump would love the Dems to be the party of "Open Borders" (or whatever the RW pejorative du jour is). The Dems should criticize Trump's overreach but avoiding repeating the same mistake they made towards the end of the first Trump regime, where leading Dems began endorsing slogans like "abolish ICE" and "decriminalize illegal border crossings."

Does feel like 76% of Republicans supporting Trump ignoring court orders to keep deporting people is a bad signal for US democracy. I mean, not the only one recently.